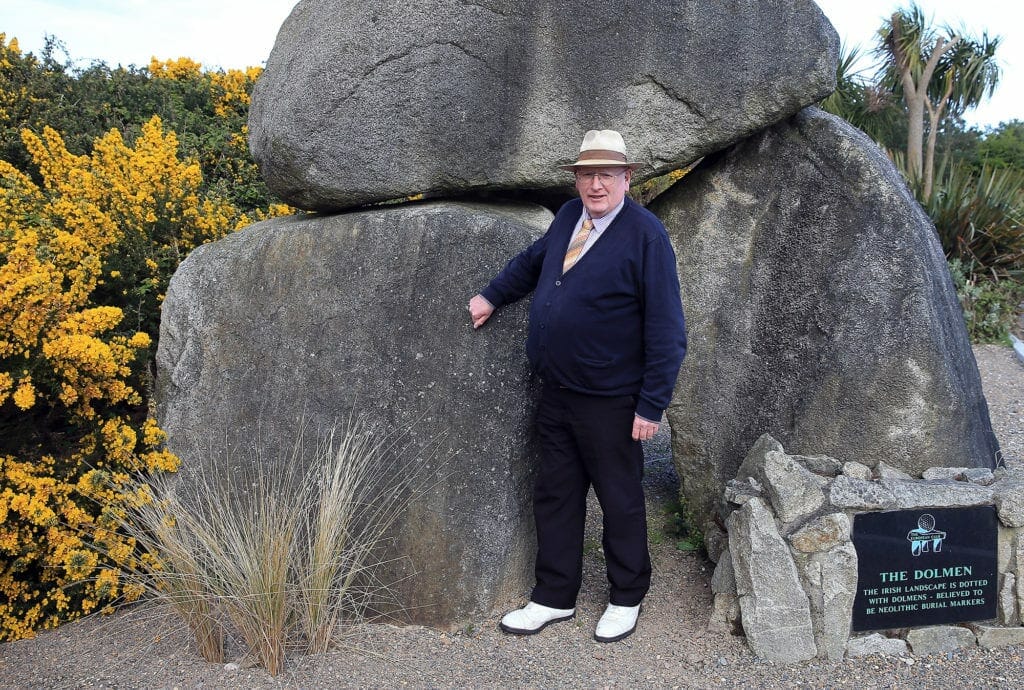

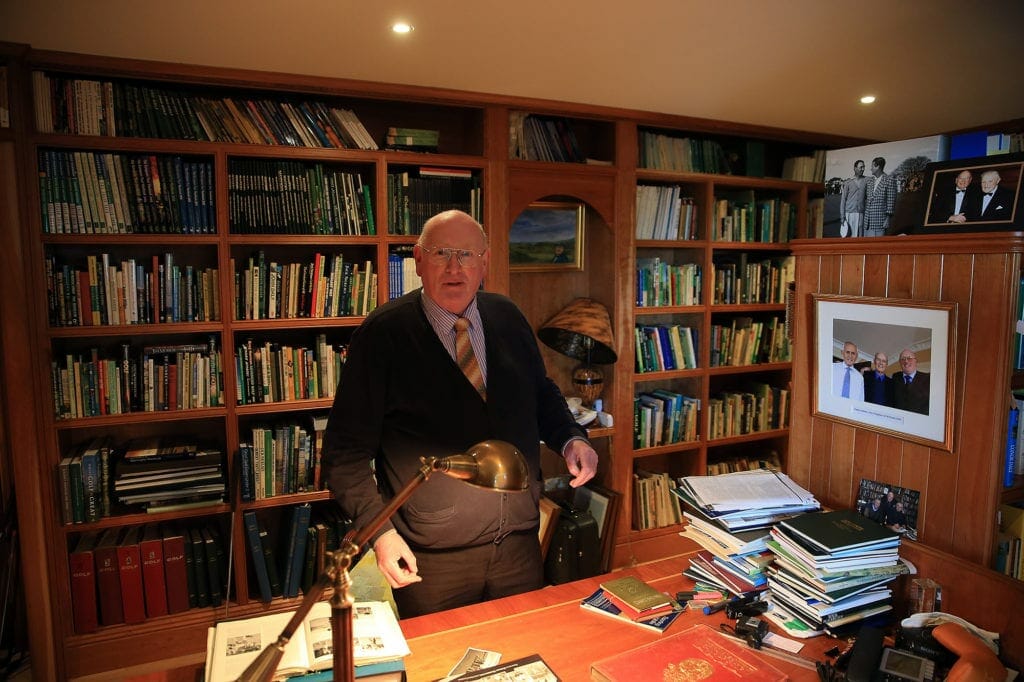

Writer, golf course designer and full-flowing fountain of knowledge, sitting down with Pat Ruddy was both a privilege and an education as we tackled all things golf, from the evolution of the game and an architect’s role in combatting it, to course rankings, encouraging player participation and improving accessibility. We milled through the cups of tea as the Ballina man, who moved to Ballymote in Sligo in 1951, began to paint a picture of just how much the game has advanced in his time alone, while I just sat back and smiled, knowing full well that for however long it lasted, my ears were in for a treat.

“In Ballymote in the 50s, we had a golf course at three different locations before I was 18,” said Ruddy. “The way golf was structured in Ireland back then, in the main, was that a small group of men, enthusiasts, would rent a piece of land from Farmer Jones, who would cut fairways so wide, but leave the rest for cattle. Of course, the boys would start losing their Warwicks and Dunlops and they’d cut it a bit more and then be evicted!

“So, it would be up-stakes, literally because you’d have stakes around the greens to keep cattle and sheep off, and over to Farmer Smith who agreed terms in the same way. The butcher, the baker, the candlestick maker, the pharmacist, bank managers, all hands on deck, drive the stakes around sites for greens, cut the grass with whatever lawnmower was available and as soon as you could find the ball, go play golf. And of course, for the luxury game we’d pop down the road to County Sligo Golf Club, so there was no hardship involved, just great adventure.”

Since those days of youth, Ruddy has been involved in almost 40 course projects, of which about 19 or 20 were undertaken from scratch, including the likes of Druids Glen and Druids Heath, St. Margaret’s and Ballymascanlon. His mark has been left at Rosapenna too, and last year’s Irish Open venue at Ballyliffin, while his reach has stretched further afield to Montreal City where Ruddy fought-off the best American designers in securing a multi million project for two courses on Montreal Island in 1999. It’s no surprise then that to this day, Ruddy’s services are sought when change is needed, though he was quick to correct me when confronted with the ‘c’ word and his recent work at County Sligo.

“I don’t call them changes you see,” he half-smiled. “I don’t want to chastise you, but I call them improvements. I never advocated change, just improvements. I like when life does the circle, you know? It did the circle a couple of times for me. One of them was in Castlecomer Golf Club, which was the first golf course I designed for a small fee, that was back in ’69/70/71, and they came back to me thirty-something years later to do a second nine. I was sort of going back to close the door and it was nice.

“With Rosses Point, where I spent a huge amount of time as a child and always dreamt about ever since and love every bit of grass on it, to have the club invite me back to what we call, ‘revitalise a classic’, was a thrill beyond words. It’s sort of going back to the start like Castlecomer, only a longer span of time. It’s a nice feeling of completion, I hope it doesn’t mean the end of life, but it’s certainly one chapter closing nicely.”

One chapter that Ruddy was always determined to start and one that stands out amongst his lengthy list of accomplishments is his own European Club at Brittas Bay. When dreams of surpassing Arnold Palmer, Tom Watson and Lee Trevino were rudely awoken by the shortcomings of his own play, his unmatched ability to identify a piece of land that would lend itself to golf soon shone through.

“I wanted a golf course of my own ever since 1958 when I read that Jimmy Demaret and Jack Burke were building a golf course of their own down in Houston, Texas. And when they called it the Champion’s Club, I liked that as a kid. The Champion’s Club sounded better than the Loser’s Club, so, the seed was set.”

Planting the seed was one thing but achieving perfection on a patch of land he could call his own didn’t come easily for Ruddy, however it was the journey to the European Club that certainly helped shape the reputable designer he is today.

“I’d tried twice previously,” he recalled, “tried to do a golf course of my own down in south Sligo and it flooded. I quickly learned about drainage. And then I was looking at Lough Rynn and was fairly advanced in negotiations, but I found that the River Shannon is dammed down at Ard Na Crusha, and you couldn’t get half an inch of drainage on the place so I backed-off that.

“I thought that was the end of the dream. But then Brittas Bay came along, and I surveyed the coast by helicopter to see where the links land was that hadn’t been turned over to golf yet. It was the first time I realised that dune land wasn’t everywhere along the coast. Because when I was going golfing, I was always going to the coast by motorcar, blindfolded, just heading straight for the mark, but from the air you could see all the different types of land, cliffs and whatnot, and only at the last meet up comes this burst of dunes.

“I pinpointed things and the one in Brittas Bay came along first. It took a couple of deals to put it together, but it was very suitable for me, it was just down the road from my home in Glenageary. It soon went from a fun thing of just doing a golf course for your own enjoyment to having the feeling that you had the makings of a very good golf place – so it became a mission, make it as good as you can. But such a mission is never finished. Like a musician is always looking for the next chord, the golf man is looking for the next nuance to the golf thing and that’ll never end, that’s the great thing. No one has ever got the perfect thing. Perfection is always around the next dogleg.”

It’s not just course designers who have been striving for perfection over the past number of years, however, with technological advancements seeing golf equipment manufacturers pushing the boundaries of the game to its limit. With the golf ball threatening to launch into orbit and tour distance averages steadily on the rise, traditional courses have been given little choice but to act to ensure their test remains an acid one to our ever-evolving game. Yet where the designer has artistic motivation when it comes to achieving perfection, Ruddy questions the motives of manufacturers whose latest releases continue to keep courses on their toes.

“Certainly the game has changed utterly,” he accepted. “Jimmy Bruen could hit the odd ball 300 yards, and Joe Carr could, and Sam Snead, and even Walter Hagen. You go back to when Tom Morris with the hickory and the gutta-percha, got the odd 300 yards up, but it was totally exceptional. The game has transformed totally every, say, fifteen years. And one has to go with it.

“You could be an old fart type of guy who would say ‘this is wrong’ because it’s eating up too much ground, but I think the healthy and correct thing to do it is to just analyse what these people have done and address it. They’re people who are doing it for money, the manufacturers of balls and clubs, they’re not doing it for love of the game, they’re just doing it so they can sell more clubs and more balls than the other guy.

“They have, in the minds of some, “wrecked the game”. In my case, I would say they’ve certainly applied huge pressures on things, but the powers that be have let them away. They haven’t defined the ball and the club. If the same thing happened in Croke Park and they had to lift out the stands at each end to accommodate the ball, it’d be incredible. But the playing field for golf has gotten bigger and bigger the way football pitches or tennis courts haven’t had to. And a golf course is a very expensive thing to provide when it gets bigger and bigger.

“The designer is the only bulwark against this, the way that he or she can set up the test to ask for skill as well as strength. But big hitting is part of the game. The best champions are always the strongest hitters, the occasional swat hitter hung in, but when I’m talking to kids now I say, ‘hit the ball like hell’ because a big drive does three things; it makes the golf course short, it makes you feel good, and in match play, it might frighten the crap out of the enemy!”

For Ruddy, golf has never been a concept of industry or business. Although he’s always made a living in it, he views it as a thing of passion. Golf is in his DNA. If he’s not playing it, he’s reading about it. But however pure his ideals remain, he can’t hide away from the fact that there’s an industry growing around his own ideas. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, he insists, but its growing reality casts a threatening cloud over the accessibility of the game that Ruddy would like to see removed from golf.

“The people with hotels, the people in tour operation, and the makers of clubs and balls. All of this is good. They’re beating the drum like mad trying to draw the attention of the world to their products, and that draws the attention of the world to golf. What’s to be watched about it – I’ll avoid saying what’s wrong about it – is that a business approach tends to seek profits and that tends to put the price of the activity up.

“People say to me, ‘are there too many golf courses?’ and I say, ‘there aren’t half enough’. Because what’s happened in every country in the last 40 years say, is that new facilities aren’t being provided by groups of men coming together as volunteers in the way I described in Ballymote, but coming largely from people inspired by money. They would like to fill a hotel, or they’d like to turn their farm into a profit-making thing better than farming, so, it’s pricey.

“Then at the other end you have a tiny percentage of the people in the country playing golf, and there’s a need for inexpensive courses in every village, so everyone can get at it. I went around the county councils years ago with my old friend Tom Craddock and I campaigned for the homeless golfers in Dublin back in the ‘60s to get a public golf course and we managed it out at Corballis.

“When I came to Dublin first, I could get golf easily because people were welcoming of me as a golfer and the first full-time writer of golf in Ireland. But I felt a huge conscience looking around that people couldn’t get into a golf club and I knew that the gate of a golf club was unwelcoming to the observation of the outsider– just like a tennis club, lots of people would never go in the gate. When you’re in, it’s so friendly but when you’re outside, it doesn’t look so friendly.”

For Ruddy, the game must move away from its elitist past and every little initiative and golf related activity can only be a good thing when it comes to raising participation levels within the sport. Yet despite a raft of ‘get into golf’ campaigns introduced by the GUI, ILGU and CGI in recent times, the veteran architect is worried that an apparent change of approach from the game’s governing bodies could undo some of this fine work.

“I think the Golfing Union of Ireland, whom I admire greatly, have changed their requirements for new clubs recently, that they have to have a golf course playable and a clubhouse of an acceptable standard – I don’t know what that is. But I think they may be moving slightly in the direction of upping the ante in terms of how much effort and money it takes to get the sport moving. I don’t want to have Pat Finn [GUI CEO] coming after me with a rusty five-iron, he’s a good guy, all the fellas are good guys. But I think they need to keep the entry standard low.

“The only reason for keeping it high that I can imagine is that those who want to have food and drink after a game of golf can have it, but we always went down to the local pub in Ballymote in the ‘50s. In Connacht you had 28 golf clubs, but only two of them, Sligo and Galway, had clubhouses built of stone. I remember in Ballaghaderreen a small shed made of metal sheeting, and you’d go in an hang your coat up alongside the purple robe of the Bishop who had gone out golfing, and you put your money in a little brown envelope if you weren’t a member of the club and put it into the honesty box.

“And you’d go out on the golf course and if you saw someone else some of the time, you’d get a fright. You’d have fellows who’d cut the grass, you could find your ball. Heaven on Earth, y’know? I think it’s very important to keep the cost of entry low so people can get in. And the Union could do well to keep an eye over their shoulder – at the grassroots. Grassroots are people who aren’t even in the game yet.”

When it comes to golf courses created with the values of the game at its core, Connemara Isles Golf Club sits proudly in Galway as an outlier to the tales of modern–day designs. Fuelled by pure willpower and miraculously funded, Ruddy says, “it came from zero, and grew like a weed out of nothing”.

“It’s a beautiful weed,” he added. “A weed is a beautiful flower in the wrong place. And I don’t mean it’s a ‘weed’, y’know? But it grew. And this has happened in my life quite a lot, something requiring millions can be done for much less if it’s taken over a number of years, and if you want it enough. And sometimes how it happens is a miracle.

“On a Monday say, one needs tens of thousands of euro by Friday, never having earned that sort of money before. But it happens. Someone comes in and gives you an advance on a job or something. I don’t know how it happened for the Lynches down there, but it’s a great example of golf that’s not pretentious but very nice – that has no great pretensions but is very civilised and homely. Where everyone who goes, no matter how they view life themselves. I’ve never met anyone who didn’t enjoy it. It helps them to step down or to touch base with ancient Irish sport in its most civilised form. It’s great.”

Given Ruddy’s obvious appreciation for the origins of the game, it comes as little surprise that when he is called in to make improvements, he does so as delicately as possible, like a restoration worker on a building of historical significance who’s been tasked with slightly modernising its creaking walls. County Sligo is one such example, the Harry Colt links that has always been close to Ruddy’s heart since he cycled as a boy 20 miles from Ballymote just to play it.

“I had a dream of being buried under the 10th tee, standing up, with a window looking down that fairway towards Benbulben, and I’d leave them a few bob to keep the window clean so I could look out there forever. So, to be invited back to look at that links was a great privilege. I always thought it was perfect you see, because I looked at it with lover’s eyes, but it’s after looking at it with professional eyes I saw, still perfection, but it can be modernised a little bit.

“I know it’s one of the greatest golf courses on earth and with things we’re doing which are mid-substantial, not earth-moving or anything, we can make it a bit more fun for the members, but hugely more interesting for the champions – because it’s a world championship links. The thinking I have is that the British Open or the Masters or even the Irish Open might never go there for geographic reasons, but there’s no reason why a golf links in my corner of Ireland can’t be ready and suitable for anything. There’s no way anyone is better than us.

“I’m very convinced myself that we will have brought this Harry Colt links much more centrefield in golf again. Harry Colt was an old pal of mine, he’s dead since ’51. He designed the old Dun Laoghaire golf course, which is just over the wall here. I could sit on my throne on a Sunday morning reading the paper, looking out at the second green at Harry Colt’s Dun Laoghaire. Now we’re again close together and having good old fights. He’s saying, ‘Ruddy for Christ’s sake leave that alone’ and I’m saying, ‘Harry, you don’t know about the modern game because a lot has happened in the last 60 years!’”

Still, even with the relentless speed at which the game continues to evolve, Ruddy can greatly admire the work of his old friend, Harry Colt as it, for the most part, continues to stand the test of time. When I put it to him whether or not he ever feels like he’s “meddling” with these great works, he quickly shoots me down, laughing, “wash your mouth out with the word meddle!”, recognising where I’m coming from but eager to reinforce the message that it’s up to the designer to stand tall against the manufacturers who continue to test the boundaries of tradition.

“I know that if Harry came today, he’d do it to today’s scale, and he’d address today’s play. Only the designers have stood up against the manufacturers and adjusted the playing field suitably to allow everyone to play, but at the same time to say, ‘big hits alone don’t conquer the world’. I’m sure Harry would be doing broadly what I’m doing. Largely what I’m doing is saying, ‘Harry stays absolutely untouched greens-wise’, but I enlarge the green left, right or back, add on to the green, as seamlessly as possible, to create some more interesting pin positions.

“If someone wants to go down and play Harry, they just put the flag where it was and it’s as before, but put the flag on Pat’s bit and the challenge is heightened considerably. But I’m happy that I didn’t even feel the temptation to change Harry, to go in egotistically and dig Harry up. I felt much more that it was a place I’d loved always, never a bad place, always a good place – that it just could benefit in addressing the modern changes with some pins, which would look well and play well.

“Of course, I don’t blame the manufacturers for everything, you have to take account of the fact that the guys are more temperate in their drinking habits now, and they’re going to the gym, they’re superior physically. They may not have as good a brain as my generation had, you guys might be a bit sillier than us, but undoubtedly the fitness of the player is awesome. I think they’re not all stupid either, they’re actually very clever – I have to tease the young fellas though, can’t have them running riot!”

Ruddy can take heart from the fact that although players are hitting the ball miles, there’s still nobody going around breaking 60 every week. The defining details of the game, golf at its rawest form, remains a golfer’s ability to get a little white ball into a faraway hole. Golf’s saving grace? “The ball is afraid of the dark,” Ruddy laughs. Indeed, it will always be a game that few, if any will ever master but Ruddy warns that it’s imperative that the powers that be ensure it’s dumbed down no more, that its values are retained and the challenge remains a stern one to preserve our sport’s soul.

“You’ve got to keep it a game of skill because if the powers that be are as weak into the future as they have been in the past, fellas could soon be attaching golf balls to rockets or something similar, but how to land the rocket at the mark is going to be the thing. The final frontier is getting it into that goddamn hole.

“I had a Yank down with me last year and he was missing his putts from five feet, he was hitting them short, and I said, ‘hit them 20 percent harder and you might have a chance’, and he said, ‘I won’t get the ones back’. I said, ‘20 percent of five feet is one foot coming back, I think we have a chance on that’. He started hitting them by the left.

“He was playing with these putters with two little golf balls on the head and I stood behind him and I noticed he was pointing them left, so I put my putter down over his two little golf balls and I said, ‘your balls are crooked, if we can straighten up your balls we’ll have a chance’, and we got them. So, there’s always a problem, if you don’t have that you have the yips, or you have bad eyesight. The number of people who can’t read a green is awesome.

“But the game remains one of skill and detail. The designer’s job is to torture people in a pleasurable way. Some people don’t like being tortured and that’s why the industry has sprung up with backfilling bunkers on some of the most classic golf courses we have. You go down and you see these little depressions where the bunkers were, and I get depressed and I say, ‘this is trying to make the game easy – a game which cannot be made easy’. It’s being made easy instead of people learning to play. I love jazz music and I got a trumpet a few years ago based on my love of jazz and the fact that this thing has only three buttons, it should be easy to play. But I can’t play it worth a crap! Cannot make anything out of it, but I don’t see anything wrong with the trumpet.”

Ruddy might not be getting a place in the brass section of the band any time soon but he remains the conductor in golfing terms at least, whether it be producing masterpieces or modernising existing ones. But how does he judge his own work, what scale does he use to quantify it? The most obvious would be the golf course ranking guides that litter media outlets around the new year as courses jostle for position to present themselves as the best in the land. But for Ruddy, although such lists can help focus the mind, they also fail to serve a purpose when you whittle down your selections to a certain few.

“I think it’s nonsense to put numbers on courses once you get within say, groups of 50. Once upon a time we’d say, ‘the 50 best golf courses on earth in terms of strength and beauty and everything else were these…’ but I think that has risen to 100 at least now. All the modern designers are dummies that have been working with knowledge of what went before, with machinery that was never there before, and they haven’t all failed to produce masterpieces, there have been new masterpieces.

“It is possible to isolate the most sophisticated ones in a group, but to put numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, is in my view, splitting hairs. To be in the group is the trick. If I was judging the Miss World contest and got to the last 50, I’d be so much in love with them all I wouldn’t know what to do!

“I think the turnstile gives you a fair indicator in many cases. But it goes wrong in a few ways, this ranking thing. I cry when I go to St. Andrews; it’s a beautiful place and it’s historic but it’s not a great golf course by modern standards. If I built it today, I would not be paid. How it still stays in the top-3 of anything I don’t know. Now that’s a safe answer unless you send your magazine to Scotland!”

Unfortunately though, when it comes to determining the best course, it’s not just reputation that’s getting in the way of merit when it comes to compiling these “well-researched” lists.

“On the other side then you have two phenomenons which are very strange. One, you have some very powerful developers of golf courses flying in the judges by private jets to their places. And this is going on, high–level entertainment which if it went on in politics it would be seen as corruption. Then the huge one – these wretched magazines, every magazine has a rating now, and one has 800 raters and the rater grates on me because no matter what his handicap is, he phones up and he says, ‘Mr Ruddy, I want to come and play your course, I’m rating the golf courses for the magazine Golfaholic’, and I say, ‘piss off’!

“If you want to rate it, that’s okay. But come in private, make your opinions. I’m not open to having my underwear hanging on the gate for you to inspect. If you want to come, do it. But instead of having Joe Carr, Peter Alice or people who know about golf judging, people are now making judgements worldwide, on value for money. If it’s cheap and cheerful, it’s good. Or the degree of difficulty – if it’s too difficult for me, a 24 handicap, it’s bad. But I think overall the right things are reasonably good, that they at least encourage thought of quality and how to judge things. But like all human endeavour, these peculiarities at the edges distort things.”

Even as his years grow loftier, Ruddy’s passion for the game persists in an eternal chase for perfection. Some of his most recent work can be seen at Murvagh Golf Club in Donegal, where he brought new life to an unsung links in our island’s land of many. It was there that a worker’s gripes rang true to Ruddy, but also where he gained a clear perspective as to how far the game has travelled in his lifetime alone, and how safe its future still remains.

“I was up there recently and one fella who was doing this job said, ‘it’s very difficult to keep going at this age, it’s very difficult,’ and I said, ‘what’s wrong?’, and he said, ‘money, money, money, money’, and I said, ‘what’s wrong with you?’, and he said, ‘members, members, members, members’, and I said, ‘how many members have you?’ He said, ‘seven or eight hundred’. I said, ‘well you should be able to do great things then. When you came out here in 1979 or 80, when you had a nine-hole course up on a hill, how many people were in the club then?’

“I knew he would have a vague memory, because he was the only one there who had been there when that happened. And he looked it up and it had 53 or 54 members. 800 should be able to keep it going well. What’s gone out of kilter with Irish golf to a degree is there’s a crisis at the moment no doubt for those who owe money, but it’s about a thousand percent above where it was in the ‘50s. The game is in a new place.

“Some people are suffering and I’m sorry for them, but the game itself has many, many more people playing on much more sophisticated golf courses in mansions of clubhouses and with transport to go between them and so on, and you can even go off to Thailand and Florida and see what’s happening over there – it’s in an awesomely better place, and the modern definition of suffering would be seen as crazy, a nirvana magi world to us in the ‘50s. So, I don’t have huge worries about it.”

Each time Ruddy spoke over the course of our lengthy chat, his memories would take him away on tangents that only served to amplify a wealth of knowledge collected from a lifetime spent in golf. And on most of those detours through golden times of yore, we’d revisit one particular place of worship that will rightly serve as an insurance policy to the playability and difficulty of our great game for generations to come; the golf hole. In its simplest form, that’s all golf has ever been; a stick, a ball and a small hole in a big field. It’s not a sport for the elite. It’s a game for the resourceful, the willing. Everyone. And it’s Ruddy’s hope that we don’t lose sight of that.

“A lot has changed but the one thing that doesn’t change is the size of the hole. That’s the torture, isn’t it? It’s right what’s happening but there’s one thing wrong; the back door to the game isn’t big enough. That’s all that’s wrong. I would like it to be a game that anyone, employed or unemployed, stressed financially or not, could get out and have an oul game. That would be Utopia. That would be the ultimate. It doesn’t have to be full-scale golf. It could be just putting, putting is golf.

“Henry Longhurst wrote a story one time about putting. He said it’s the one part of any major outdoor sport that anyone could be world champion at, because it requires no strength and very little imagination. In fact, he said that total lack of imagination might help a lot. And he said that a little old lady on a public putting green in Blackpool on a wet summer’s day, wearing her mac, and her southwestern hat, and her handbag tucked under her arm, could be happy knocking them in from 6 feet until a golfer came by and said, ‘it’s difficult, isn’t it?’

“And then she was toast, like the rest of us!”

This article appeared in the June 2019 edition of Irish Golfer Magazine. Click cover below to view full issue.

Leave a comment