September 11, 2001. The day terrorists flew two passenger jets into the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers only for thousands to be directly affected by the disaster.

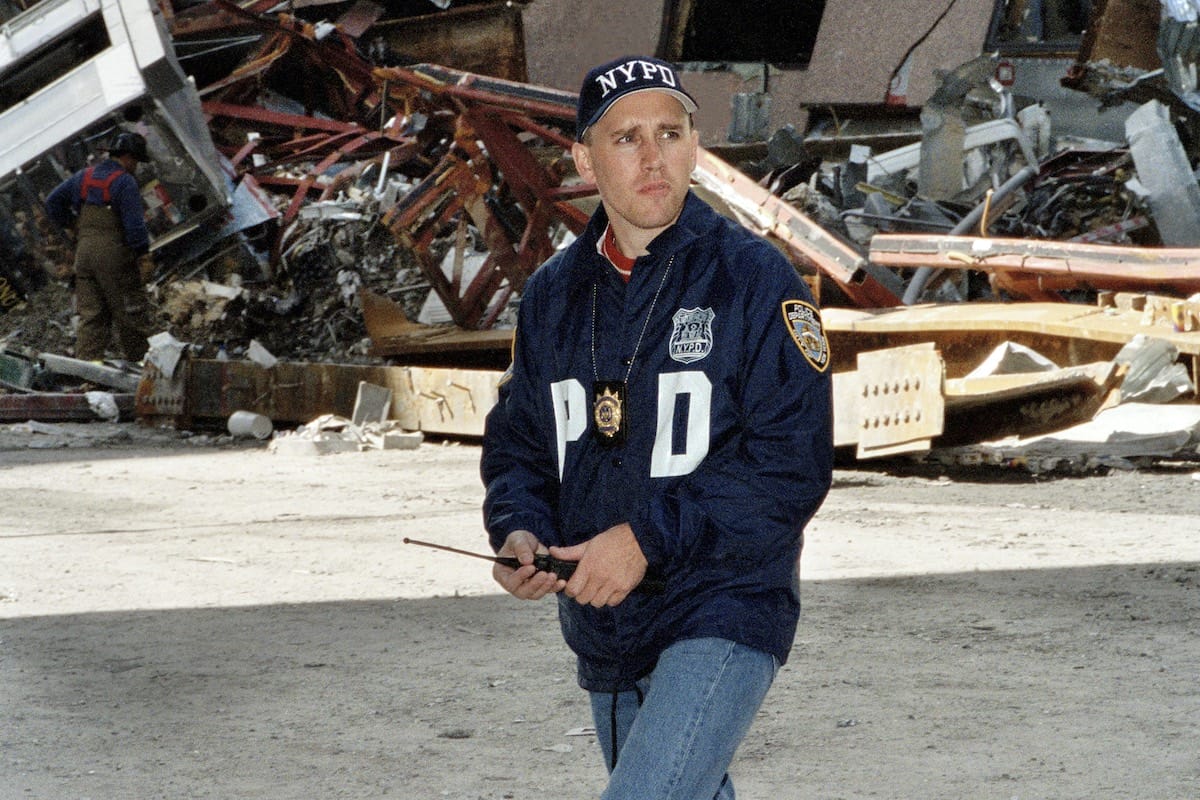

Two of them were then NYPD captain Paul McCormack, a GAA-loving native of Ballybofey, County Donegal, and Dublin born photographer Nicola McClean.

McCormack, at the time an 11-year decorated veteran of the NYPD rushed to the scene, as did so many police, Fire Department and first responders when the calls came for assistance.

Aged 32, the commanding officer of the 41st Precinct threw himself into the rescue effort, and went on to spend three months at Ground Zero, sifting through the rubble, looking first for survivors and then as part of the recovery effort.

Gruelling, emotionally draining work, but all that had to be set aside. Little did he know that there was to be an additional personal cost – his sight.

In the time McCormack and so many others were engaged in their grim tasks for so long, the toxic fumes and chemical residue that were released in the collapse of the buildings silently attacked their health and wellbeing.

Many subsequently got cancer or suffered other ailments that shortened life spans and caused death and disability.

In Paul’s case, he gradually lost the gift of fully functioning vision. One of the ways it showed up was in his golf, a game he had taught himself to play in his early days as a young cop.

“The thing with my eyes is, they think it’s a hereditary thing that kicked in because of the toxins. So it’s a hereditary condition that kicked in and my central vision is all gone.

“When I started not being able to see the ball, it got embarrassing.

“When you’re with two or three guys and you’re looking straight at the ball but you can’t see it and you’re like ‘guys, where’s my ball,’ and they’re saying ‘It’s straight in front of you, what are you talking about?’

“I’m like, ‘I can’t see it’.

“I was slowing everybody down. I just gave it up, cold turkey. I put the clubs away and said I’m not doing this again. That was in 2001-2002.

“After that I finished up in the police department in 2010.

“I had to retire. I couldn’t drive, couldn’t shoot anymore, so I had to give up the job I loved and moved back to Ireland with my wife Nicola and kids,” said McCormack.

A keen and active sportsman, Paul had played hurling and Gaelic football for Seán MacCumhaills of Ballybofey and represented Donegal at minor level.

On emigrating to America in 1986, he linked up with the GAA and played for the Donegal team in New York.

But after 9/11, those options were no longer available to him.

In the meantime, Nicola, who was working as a photographer covering the 9/11 disaster, had also been affected by the loss of life and the pain of the bereaved families.

Ultimately Nicola and Paul – they were dating at the time of the Trade Center attacks and later married – put together the internationally renowned Ground Zero 360 Remembrance Exhibition of photographs, artwork and artifacts.

Currently the Exhibition is on show at Houston Baptist University until next January.

“We’ve been at it for 11 years now and we’ve been to over 40 cities around the world. It’s grown every year. We’re very honoured to do it, both of us.

“We lost a lot of police and fire fighters in 9/11 and we’re just honoured being able to remember them and their sacrifice,” said Paul.

And what about golf? Gone forever out of his life? That’s what he thought until a friend asked him to make up a team in a fundraiser at Howth Golf Club in 2015.

“There was a fourball that one of the guys pulled out on the day of the tournament, and they needed a fourth man to fill in.

“I said ‘Guys, I’m blind, I can’t see anything. I haven’t hit a ball in 13 years.’ “They said ‘Don’t worry about it, we’ll follow the ball, we’ll take care of it for you. We just need you to fill out the team.’

“So I had my old clubs, a really old set of clubs and took them out, dusted off the cobwebs, and I ended up getting three or four pars. I scratched a lot of holes but I wound up hitting it pretty decent not having hit a ball in 13 years,” he said.

From that outing came a suggestion from a friend to join the Irish Blind Golf Society.

“I ended up joining, and the first actual big tournament I played in was in 2016, the US Open, and I won the US Open.

“The same year I played in the British Open and I won the British Open as well.

“So I’ve won two US Opens and two British Opens. And I’m the current US National Champion,” he said

At club level – he is a member of The Links Portmarnock GC – Paul is renowned for his performances in club ‘majors.’

Three years ago he won the President’s (Cecil Ryan) Prize with 41 points off a 23 handicap.

This year, he finished runner-up with 39 points off a 25 handicap in the Captain’s (Donal Duggan) Prize.

Recently I had the opportunity to play alongside him in a Wednesday singles competition at the club. Playing off 26 on the day, I had the handsome total of 21 points.

Paul McCormack, blind golfer, playing off 24 handicap, 38 points.

Had even one more putt dropped – and on one hole the ball stopped just a centimetre short – he would have had 39 points and beaten the field of able-bodied golfers in the competition. It was fascinating watching him in action.

To play, Paul goes out in a buggy with a guide. On the tee he just needs to know he’s set up correctly for direction. He wants to be sure his tee is straight, and that the centre of the clubface is behind the ball.

After that, no second guessing. Swing and hit. Closer to the green, he keeps it simple.

“I don’t like messing around. I just get set up. The thing with me is I don’t want to know if there’s any hazards. Just tell me what the distance is. Give me the distance to the pin, give me the distance to the front of the green and don’t tell me if there’s any hazard left or right,” he said.

For putting, his feet and body give him good feedback on the slopes.

He bends right over the ball, moves his head so he can get some view of the ball with his peripheral vision, and just makes his putting stroke.

Paul also maintains the GAA connection by being a mentor to the Beann Eadair club’s under-16 team.

It’s a full life, and one Paul embraces with a hundred per cent enthusiasm in spite of his disability. He is categorised as B2, the second highest grade of visual impairment.

“I have no central vision,” he explained.

“My central vision is gone. I have about 30 percent vision. My peripheral is ok. My right eye is worse than my left eye. I have zero central vision. It’s like a fog.

“If I look at your face I can’t see your face. I’d have to be right up, a foot from your face to see what you look like. It sucks but you live with it. It’s life and that’s what it is.

“Things could be a lot worse. I’m not complaining. You’ve got to get on with life. I’ve got five kids and they don’t want to hear any crying from their old man.

“They want me at their sports events, they want me to spend time with them and do what a father does, so let’s do it and do the best I can with it.

“It’s full on. I’m a big GAA man. I help out with the coaching of Ben Eadair under 16 team. I’ve been with them for about eight, nine years now from when they were seven or eight years old.

“If I’m standing on the sideline I can’t see anything, so I have a high powered pair of military grade binoculars, and that enables me to see some of what’s going on.

“Again, you could get frustrated at it. The players all know I’m visually impaired.

“They respect it and I try to do the best I can. I don’t want to be treated any different to anybody else. I just do the best I can. You learn to live with it. You do what you’ve gotta do.”

For the past 18 months Paul has played a central role in the planning and staging of The ISPS Handa Vision Cup, the equivalent of the President’s and Ryder Cup for Blind Golfers.

This year’s event took place at TPC Sawgrass from September 20-23 between North America and The Rest of the World.

Teams of 14, including two women golfers on each team, competed for the Cup which the Rest of the World side won in 2019 at The Links, Portmarnock.

Leave a comment