Intro

As men’s professional golf emerged from its somewhat quaint and sedentary early epoch with the Mark H McCormack-inspired ‘Big 3’ of Palmer, Player and Nicklaus taking advantage of a post war increasingly affluent baby-boomer country club demographic and the rollout of colour TV, by the time Eldrick Tont ‘Tiger’ Woods appeared like a dervish in the last knockings of the 20th century, there was certainly further scope for the commercialisation and monetisation of the elite, professional side of the royal and ancient game.

And how.

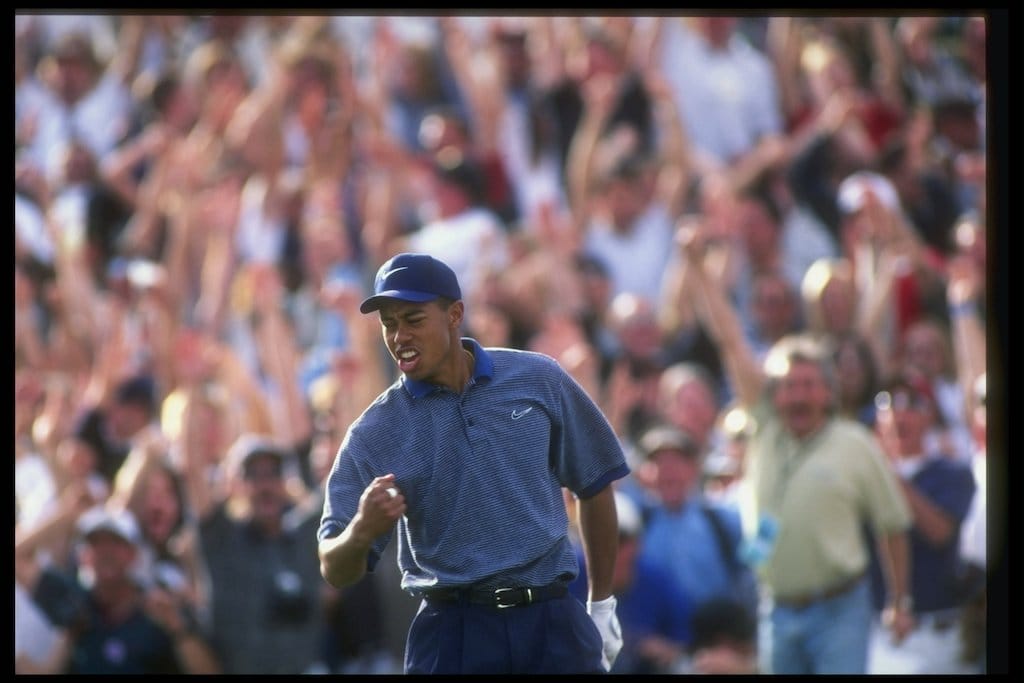

Across the board, from prize money and appearance fees to player endorsement income, media rights sky-rocketed exponentially as the swashbuckling mixed-race Californian-born phenomenon hit the ground running, his influence on the finances of the PGA TOUR and its smaller cousins around the world soon bolstered beyond their wildest dreams, irrespective of his highly-selective choice of tournaments, personal peccadilloes and the subsequent decline of his injury-ravaged physique.

Riding on the back of the great man’s dominant exploits, and unprecedented successes, every aspect of the game would benefit from the ‘Woods effect,’ from participation numbers, media rights and golf equipment and apparel sales all went through the roof, as Woods-inspired ‘Golf-fashion’ seduced recreational players and fans all around the world.

Bunker Mentality examines the commercial bounce from the sporting impact of one of the most significant sporting phenomena of modern times, and, while acknowledging his short and medium term legacy is assured, supported by evidence, but with commercial comet now in terminal decline, concludes that when Woods is rightly remembered as golf’s greatest bankable asset, his influence is on the wane, and with no obvious successor currently capable of taking on his towering presence, universal appeal and magnetic charisma, and with the rival LIV Golf far from ‘dead in the water,’ the mainstream men’s pro game may discover that the ‘Tiger Economy’ was, when set in the context of one-hundred-years of professional golf, the best years of its long and colourful history.

Only the passage of time will tell.

For much of its early years of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries, on the east coast of Scotland and beyond, a few select places around the UK linked largely to the aristocracy and military top brass, golf was the preserve of the entitled elite and even once marginally more accessible to a few members of the working class who excelled in the early iteration that was the epitome of the royal and ancient game, playing for money – mostly modest wagers made between rivals – was still considered by those who ran the fledgling sort to be rather uncouth and unsavoury.

Even once the embryonic Open Championship got underway at Prestwick in Ayrshire, Scotland in 1860, there was not a penny piece in prize money on offer; indeed, it was four years before princely sum of a US$10 prize fund was put up, dusty records revealing Willie Park Snr beat arch rival Old Tom Morris to pocket the first prize of US$5, hardly a King’s Ransom.

It was 1892 before the US$100 barrier was broken, ironically English amateur Harold Hilton earning the title of Champion Golfer of the Year – but due to his amateur status, he eschewed the 35-dollar winner’s fee – content it seemed to be taking the Claret Jug home, the total prize fund was still only US$500 when ‘Silver Scot,’ Tommy Armour banked an unprecedented US$100 for his victory at Carnoustie in 1931, less than a century ago.

Golf at both professional and recreational levels remained in effect a niche, cottage industry, largely the preserve of the entitled middle classes either side of World War II. Making a sustainable living out of playing golf was far from rewarding. American Walter Hagen, considered by many to have been the greatest player of the inter-war years won just US$75 for each of his four Open Championship victories, while, immediately after the cessation of hostilities, the great Bobbly Locke accumulated just US$1,900 for his quartet of Claret Jug wins.

Even the late, great Peter Thomson, five times an Open Champion – including three-in-a-row in the 1950s, to this day, even in the era of Tiger Woods domination, still a record of the modern era – amassed only US$5,500 from his unprecedented domination and retention of the Claret Jug.

Post war, in 1946, American icon Sam Snead took away the Claret Jug from St Andrews, his first prize of US$150 out of the first-ever US$1,000 prize fund, but men’s professional golf remained a career fraught with uncertainty and far short – even allowing for inflation – of the eye-watering sums on offer today.

The legendary Bobby Jones never left the amateur ranks, while golf’s grand master-in-waiting, Jack Nicklaus only turned professional after apparently weighing up and contrasting the risks and rewards of pro-golf with a career selling insurance and, thankfully the Golden Bear chose golf and the rest is history, including a record-breaking 18 ‘Major’ championship wins.

But a young, golf loving lawyer out of Columbus, Ohio by the name of Mark H McCormack, himself a keen and competent golfer had an initial, bold vision of developing the commercial opportunities arising out of men’s professional golf.

Seemingly with all his ducks in a row – a burgeoning US post-war economy, an emerging ‘baby-boomer’ generation, an increasing awareness of the importance of brand awareness and product marketing, an embryonic sports marketing sector and, crucially, colour TV, not to mention the sumptuous talent in the form of the ‘Big 3,’ comprising Arnold Palmer, Gary Player and Jack Nicklaus – through his International Management Group (IMG) vehicle, set about creating the first transformative coming of men’s professional golf as a credible and viable sales and marketing device.

Yet, compared to the turbo-charged Woods era which began three decades later, McCormack’s enrichment of his Holy Trinity of Nicklaus, Palmer and Player was modest by comparison, the trio earning less than US$5m between them, allowing for inflation would have been worth around US$25m a today’s prices and less than US$10m each, an insultingly poor reward for the 159 PGA TOUR titles and 34 ‘Majors’ between them.

Compare that with the 200-plus PGA TOUR players each earning over US$10m last season, many of them without a tournament victory, let alone a ‘Major’ title, Jack Nicklaus earning a meagre US$144,000 for winning the 1986 Masters, becoming the oldest man at 46-years-old to win a ‘Major’ title, that’s the equivalent of US$393,000 at today’s prices, Scottie Scheffler banking almost US$2.5m for winning the same tournament 36-years-later, every member of the Top-10 at Augusta National exceeding the inflation-adjusted sum Nicklaus scooped in 1986.

But, enough of the historical context, but it’s certainly safe to make one of two assessments of these monetary sums, either the ‘Big 3’ were hugely undervalued and almost criminally under-rewarded, or that the class of contemporary players are, by comparison, richly and vastly overpaid. All of which brings us to 1996 / 97 and the emergence of a young Californian by the name of Eldrick Tont ‘Tiger’ Woods; already a very rich young 20-year-old before a shot was struck in earnest, courtesy of lucrative equipment and apparel deals with Titleist and Nike said to be worth US$20m and US$40m respectively.

That Tiger Woods has had a profound effect on almost every aspect of golf, professional and recreational is beyond doubt; the PGA Tour saw US$101 million in total prize money for the 1996 season, the same year Woods turned professional, rising to US$292 million in 2008, and to a whopping US$315m for the current 2022 / 2023 season, Woods himself earning almost US$120,954,766 at the time of writing and, crucially, amidst the clamour surrounding arguably the most exciting young sportsman and a bidding war between big brands for a slice of the action, creating a much bigger and more financially valuable cake, exponentially and directly raising the earning potential of every PGA TOUR player, and, indirectly giving a financial leg-up to players on both the European Tour and the LPGA circuit.

It can surely be no coincidence that no fewer than 55 current PGA TOUR players have earned in excess of US$25m, some, like American Jim Furyk, second on the all-time career money list with US$75m, Australian Adam Scott, fifth with US$60.2m and Englishman Justin Rose in sixth place on the all-time career money list with US$59.2m at least have a single ‘Major’ title against their name.

But there are others who have clearly been pulled along in Tiger’s slipstream, players like Matt Kuchar (US$56.1) and Rickie Fowler (US$43.3m) and Billy Horschel (US$34.1m), all very good players with multiple Tour titles to their name but are yet to win even one ‘Major.’

Even Phil Mickelson, now consigned to the margins of mainstream men’s professional golf, and arguably Tiger’s nearest rival and sworn adversary heaped fulsome praise on his opposite number’s contribution to the game of golf, Tweeting in 2020, “Dear Tiger, Thank you for all that you’ve done for this great game of golf. No one has benefited more than me and I just wanted you to know I appreciate you and all you’ve done. That’s all. Thank you.”

And that appreciation was fully-deserved, Mickelson, having gone toe-to-toe against Woods throughout their respective careers during a ‘golden era’ for men’s professional golf; ‘Lefty,’ as he is affectionately known won US$94,955,060 on the PGA TOUR, second only to Woods, his name and playing record, like other LIV Golf defectors including Dustin Johnson (US$75m) and Sergio García (US$43m), expunged from the record.

But it is surely the overall impact of Woods’ towering presence over a quarter of a century in general and in particular, his impact on annual prize money on offer on the PGA TOUR that defines Tiger’s legacy; total prize money in 1996, his first year on tour was a relatively meagre US$65,950,000, rising to US$249,650,000 in 2005, US$340,000,000 in 2017, US$421,800,000 in 2022 and at least US$563m this term, a staggering 754% uplift over the course of a truly remarkable career to date.

Former PGA TOUR Commissioner Tim Finchem, whose tenure straddled what has come to be known as, ‘Peak Tiger,’ is in no doubt as to the influence of his star attraction, commenting shortly before he stood down in 2016:

“I have to put him down — I love Jack Nicklaus beyond belief – but I have to put Tiger down as probably the greatest player ever to play,” while Finchem’s successor Jay Monahan agrees with his former boss, saying on ESPN, “Whenever Tiger Woods is in contention or just playing a tournament, he raises the awareness of our sport,” adding, “He has had a hugely significant impact on all aspects of the sport of golf,” concluding, “He’s such an iconic figure, who has worked with the industry and, going forward, he has had a tremendous both on and off the golf course.”

Meanwhile, while the ’Tiger Effect’ has most directly impacted on the PGA TOUR correspondingly, both the European Tour (now the DP World Tour) and the LPGA Tour have benefitted hugely – if indirectly – from Woods’ pulling power and earning potential.

Despite Woods never joining the Wentworth-based outfit and playing only on its schedule in the guise of co-sanctioning between the PGA TOUR and DP World Tour, such as the four ‘Majors,’ and WGC events, its prize funds have spiralled upwards, thanks to some extent on the back of Woods helping raise the bar stateside; total annual European Tour prize money rising from €85,300,405 in 2000 to at least €199,529,595 in 2023, due in no small part to the marketability of Woods.

Guy Kinnings, DP World Tour Deputy Chief Executive, Ryder Cup Director & Chief Commercial Officer of the DP World Tour commented, “In my opinion, there is no question that Tiger Woods has been the single most significant factor in the growth, in the appeal and in the value of golf as a sport.

“Analysis reveals that prize money across the PGA TOUR and the European Tour (now the DP World Tour) increased exponentially between Tiger making his professional debut in 1996 right through to the present day, alongside the growth in sponsorship investment, consumer revenues and media rights for our sport. None of these statistics are a coincidence.”

Former IMG Global Head of Golf, Kinnings concluded, “His 110 professional victories, including 15 ‘Major’ titles and 18 World Golf Championship triumphs, speak for themselves and attest to his dominance inside the ropes, while, as he enters the latter stages of a truly stellar playing career, he will remain a huge influence on both the financial and commercial development of the game.”

Meanwhile the LPGA Tour also benefitted indirectly from the ‘Tiger Effect,’ its annual prize funds rising from US$17.1 million in 1990 to US$36.2 million in 1999, falling back to US$41.4m before, in 2010 recovering to US$75.1m and US$104m in 2020 and 2023 respectively, the most successful and competitive women’s circuit, in part at least, riding on the back of the Woods-driven PGA TOUR sponsorship success story.

Woods has helped his fellow leading professionals in other ways too, especially in the areas of appearance money and endorsement contracts, turbocharging the market in both. In his pomp, Woods was able to command a fee of up to US$2m per appearance as tournament organisers and their sponsors got into a bidding war in order to have the long-time world number one in their field, enabling fellow Top-20 players and their agents to demand high six-figure and on occasions, low seven-figure sums to play and generate maximum pre-publicity along with optimal TV viewing figures.

Even so, any tournament not featuring golf’s number-one drawcard was seen to be devalued, but, when he was in the field and especially in contention over the weekend, the ratings, especially with Woods on the charge over the stretch, PGA TOUR golf delivered unprecedented audiences which, according to broadcaster CBS, would see TV ratings drop by between 30% to 50% if Tiger was not in the field or out of contention.

Similarly, with Woods able to command unprecedented multi-million-dollar endorsement contracts, with premium brands such as Rolex, the Swiss luxury watch brand reportedly paying him US$10m per year to promote their products, with other, lesser players also cashing in, amongst them Justin Thomas, Jon Rahm, Adam Scott and Hideki Matsuyama joining him in the Rolex stable, albeit at a significantly reduced level.

Furthermore, while there is mostly only circumstantial and anecdotal evidence that the ‘Tiger Effect’ had played a part in the exponential increase in golf participation, fan engagement, media time and space and on skyrocketing sales of golf equipment and apparel between 1997 and 2022, there can be little doubt that Woods, once again, has helped drive up sales of equipment and clothing by bringing ‘sports fashion’ to the fore.

The World Golf Report 2023, a study by Golf Datatech and Yano Research Institute, reported that, globally, the golf equipment sector was valued at US$11.5 billion and the apparel sector just below US$9 billion in 2021, a total of US$20.5billion in sales worldwide, a huge inflation-adjusted increase of over 500% on the sector before Woods turned professional in 1996, helped not only by non-golfers purchasing sports fashion products as casualwear and died-in-the-wool golfers changing and upgrading their golf clubs much more frequently than before as manufacturers like TaylorMade and Callaway seduced consumers by ringing the changes with new, must-have equipment.

But what is less clear is whether Tiger Woods has shifted the dial on mass participation in the sport. According to the US-based National Golf Foundation, in 1995, just prior to Tiger’s arrival on the PGA Tour, there were 24.8 million committed golf enthusiasts, namely those who play eight-or-more times each year, finding that, by the start of the new Millennium, that number had risen to 29.9 million, a 20% increase, but, by 2021, this had fallen back to 25.1m

But this data is at variance with the global picture painted by the R&A in its 2021 Worldwide Golf Participation Report.

The R&A revealed that, since 2012, 5.5m new regular golfers have been added, up from 61.6m to 66.6m, suggesting the NextGen cohort is keeping pace ahead of those giving-up on the game, but it is the first coming of Tiger Woods – 1997 – 2009 – when he was utterly dominant in men’s professional golf that saw, anecdotally (no accurate data from that period is available) at least, burgeoning engagement with and participation in the game he helped transform is slowly but surely on the wane.

Perhaps the best that can be said is that Tiger Woods has brought golf to the masses, creating interest amongst those hitherto disconnected from the game and dragging his sport into the mainstream of sports entertainment and that, were it not for him and his sheer force of nature, golf at both professional and recreational levels would be in a much worse state than it finds itself today.

The unprecedented wealth Woods has helped create may have spawned an entire generation of professional players who have not only become super-rich beyond their wildest dreams, a cohort of impressionable and mercenary young men who may have developed an unrealistic and unwarranted idea of their own self-worth and earnings potential and who may have been seduced by the millions available on the breakaway LIV Golf League, for some, a compelling opportunity to earn much more for considerably less.

As for the future of golf in an imminent Tiger-free zone, his very presence and his undoubted charisma and appeal slowly drifting away, there is no clear heir-apparent; despite a raft of world class players such as Rory McIlroy, Jon Rahm and Scottie Scheffler, Woods was, is and will continue to be unique, a one-off, professional golf’s undoubted pack leader and alpha male.

The global head of a major sports management agency which is heavily involved in professional golf and a leading light in the European Sponsorship Association, who did wish to be named, reflected on the career and legacy of the 15-time ‘Major’ winner commented: “It goes without saying that Tiger Woods has, almost single-handedly and by the sheer weight of his prodigious talent and force of nature helped overhaul every aspect of the game – tournament prize money, TV ratings, grass roots participation and equipment / apparel sales – from relative stagnation when he started out as a rookie professional in the late 1990s to a much healthier position as he reaches the nadir of his remarkable career.

“But, while he is still a figure of enormous and unprecedented significance, it is becoming increasingly clear that Tiger Woods can no-longer play anything close to a full schedule, and his influence will inevitably dissipate over time, and, with no obvious successor to Tiger’s mantle, the PGA TOUR will need to work much harder simply to stand still in an increasingly challenging commercial landscape, and with its USP at best, on the margins, at worst, out of the frame.”

In conclusion, almost single-handedly, Tiger Woods, in his 25-year career as professional golf’s undoubted poster boy, has not only made himself the sport’s first-ever billionaire, but, perhaps more importantly, has dragged his sport in general and the men’s professional game out of relative mediocrity and obscurity into the sporting and cultural mainstream, a global icon, one of the few, like Pele and Ali, ‘Tiger’ needs no other explanation.

But, as he prepares to leave the competitive stage and with all his exploits consigned to the archive, the challenges created by the men’s professional game largely having all its eggs in the one basket become ever more apparent; perhaps he will continue to lead golf in some shape or form, but, all in all, he is almost an impossible act to follow and, with fraught issues remaining unresolved with the controversial LIV Golf League, consolidating what he has delivered and leaves behind, let alone move ahead from the high-water-mark that is his legacy remains the greatest challenge facing the game going forward.

Leave a comment